Historical Background

THE FIRST RECORDED MENTION of a memorial to McCrae’s was made by D.M. Sutherland in April 1919, when the surviving officers of McCrae’s Battalion gathered at the North British Hotel in Edinburgh’s Princes Street for a grand reunion dinner. Sutherland was an artist by profession with an artist’s eye for metaphor and symbolism. A traditional Scottish cairn, he suggested, representing courage, dignity and fundamental strength of character. The materials should be Scottish and the workforce Scottish craftsmen, ideally drawn from the ranks of the battalion itself.

The idea was well received and officially endorsed at the next meeting, the first Reunion Dinner proper of the entire battalion, which was held at the Victoria Hall in Leith Street on 15 December, the anniversary of their mobilisation in 1914. Early the following year the 16th Royal Scots Veterans’ Association was formed with former A Company private, Andrew Riddell as organising secretary. The Association had little in the way of funds; many of its members were suffering from physical impairment or unable to find permanent employment at their pre-war trade. If the commemorative proposals were to succeed, help would be required, so an informal approach was made to Edinburgh Corporation. McCrae’s was the 2nd Edinburgh City Battalion and had represented the capital in France and Flanders with no little distinction. But Riddell was disappointed. Further attempts by Sir George McCrae and other influential citizens fell on equally deaf ears. In the mean time the Tyneside battalions of 34th Division had acquired a plot of land outside La Boisselle and were pressing ahead with a plan to build a substantial memorial seat on the site.

Sir George was uncomfortable with compromise, but he and his comrades were obliged to accept the inevitable. Their plans were scaled down to a more affordable ‘memorial tablet’ in Edinburgh’s High Kirk. It cost £1,000 and the monies were raised mainly from the ranks of the Association and the families of the lads who didn’t come home. It was unveiled on Sunday 17 November 1922, a limestone relief of St Michael astride the slain Prussian dragon. A letter from Field-Marshal Earl Haig was read out during the ceremony. It specifically mentioned the battalion’s deeds on 1 July 1916, proving (if nothing else) that the former Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force had a better memory than the assembled councillors and bailies of the City of Edinburgh.

At the end of June 1926 D.M. Sutherland travelled back to the Somme for the 10th anniversary of the opening day of the battle. 1 July found him at La Boisselle on the old British front line. Later that morning he attended the unveiling of the memorial to the 34th Division in the fields just behind the village. Placing his tongue very firmly in his cheek, he wrote home to McCrae:

The 34th Division Memorial is not an impressive or dignified monument. In the first place the site is poor. It is hidden away from the main road by rising ground and farm buildings and, for a monument that has its position in a big stretch of undulating country, it is a mistake to choose an underlife-sized bronze figure on a light granite base. It simply fritters itself away among the accidental spots on the landscape. What is required is a big block shape – a cairn or a broch – something with a sense of permanence about it and simple dignity.

D.M. was more impressed by the Tyneside Memorial Seat, which he described as ‘important’. Through the mist of decades it’s impossible to read the letter without sensing his keenness to design and build something equally important for McCrae’s.

D.M. also approved of the 51st (Highland) Division Memorial at Beaumont Hamel, which had been unveiled in September 1924. There is nothing ‘underlife-sized’ about Sergeant-Major Bob Rowan as he stares defiantly out over Y Ravine. The sculptor, George Paulin (whom Sutherland knew), came from Clackmannanshire and insisted on using blocks of Rubislaw granite for the rugged base. The Gaelic inscription tells us that on the day of battle, it’s good to have friends. The friends who died there in November 1916 are scattered through a dozen nearby cemeteries.

***

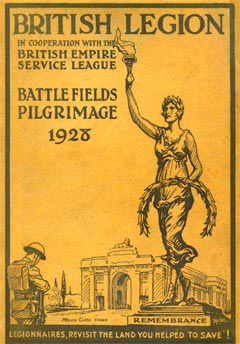

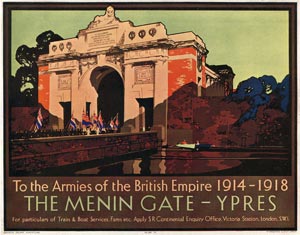

The first large-scale battlefield pilgrimage took place in the summer of 1928. It was organised by the British Legion like a military operation, with veterans from different parts of the UK divided into ‘companies’ and allotted ‘billets’ near the places they had fought. The previous year Viscount Plumer had inaugurated the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing at Ypres and the following decade would see the successful completion of a host of commemorative initiatives – from the grand scale to the small. Lutyens’ towering Thiepval Memorial was inaugurated in 1932, as was Albert Toft’s more intimate 41st Division figure in the village of Flers; Walter Allward’s breathtaking Canadian National Memorial at Vimy was unveiled by Edward VIII in 1936.

That same year a group of twenty McCrae’s veterans, led by Andrew Riddell, journeyed out to the Somme for the twentieth anniversary of the first day of the battle. As they wandered through towns and villages dotted with newly minted memorials, the absence of anything dedicated to their own battalion had never seemed so hurtful. One disillusioned member of the party told his wife tearfully that they seemed to have been forgotten. ‘It’s not for me; you know that, don’t you? It’s for the boys who didn’t come back.’

In 1939 another artist enters the story. Adolf Hitler had served on the Somme during the Great War and enjoyed the experience so much that he was determined to return. It took a while to dislodge his followers and the 1946 pilgrimage was cancelled. Three years later Andrew Riddell passed away and the leadership of the Veterans’ Association fell to Sandy Lindsay, who’d risen to the rank of CSM of B Company at the age of 20 following the action at Intermediate Trench, near High Wood, in August 1916. Lindsay, now Clerk of Works at Fettes College, was a resolute writer of letters and renewed the Association’s efforts to gather support from Edinburgh Corporation and the Regiment in time for the 1956 commemorations. Again he was disappointed.

In 1964 the BBC Tonight show produced its landmark 26-part documentary series on the Great War, which included numerous interviews with surviving participants and an untold wealth of still photographs and moving film. An average of eight million people watched each episode and the series signalled the start of a reawakening of interest in a war that had been overshadowed by the struggle against Nazism. Lindsay charged his pen and prepared for another assault on officialdom, conjuring the spectre of civic embarrassment if the 50th Anniversary came and went in the continuing absence of fitting recognition for Edinburgh’s battalions. But no one was listening. When the 16th Royal Scots Veterans Association was finally disbanded in 1976, it closed with a good deal of unfinished business.

***

By the mid-1970s the Western Front was beginning to attract a new generation of battlefield tourists, many of them descended from men who’d served there during the war. They came on their own or in small organised groups, sometimes clutching a linen trench map that had last visited the area in 1916. The route of their itinerary was defined by the great memorials – Tyne Cot, Ypres, Ploegsteert, Vimy, Arras and Thiepval – and punctuated by itinerant ramblings off the beaten track to locate some tiny cemetery where a lost uncle or grandfather lay waiting for someone (at last) to come calling.

On 1 July 1978 a new destination was added to the ‘official’ list, when English businessman Richard Dunning purchased Lochnagar Crater, on the south-eastern flank of La Boisselle in order to protect it from development. The previous year Lochnagar’s twin, Y-Sap, had been filled in with a view to building houses on the site. Dunning saw the potential loss of an irreplaceable piece of history – the largest crater ever made by man in anger. ‘Lochnagar’, in Richard’s words, ‘is a vast, open wound on the battlefield, symbolising the eternal pain, loss and sorrow of millions of grieving people throughout Europe. A lost generation of good, gifted and innovative young men whose loss we still feel today. I urge you to come and stand at Lochnagar and, in doing so, commemorate those who fell there. But to do so, not simply by remembering them, but by seeking to make the world that they were so cruelly denied a much more peaceful, forgiving and loving place. In their memory and in their honour.’

Andrew Riddell and his pals would have agreed with every word.

1978 also saw a blossoming friendship between several elderly veterans of McCrae’s Battalion and a young Edinburgh University undergraduate. I had already met Walter Scott, the oldest surviving member of Heart of Midlothian’s 1914 playing squad and was deeply immersed in the study of the Great War. I met most of the McCrae’s lads at Tynecastle Stadium and distracted them from the mercurial wizardry of Bobby Prentice by asking daft questions about trench rations, rifle grenades and their long-forgotten Colonel. ‘Ah, the Colonel,’ they would sigh. ‘Now there was a man!’

I first became interested in the war when I was about eight and I spent my teens ‘gathering’ local veterans, talking to them, listening and looking at their precious photographs. (‘See that lad in the back row? No, not him. The one third from left. Yes, him. He was 18, same age as me. I saw him fall. Just crumpled in front of me. They never found his body. He was my pal. We used to sing together. Barbershop, four of us. I’m the only one who came back.’)

The McCrae’s boys were different: there was an electricity about them, a combination of unalloyed pride and bitter anger. Pride in their battalion – which was always ‘the best’ – and anger at a world that had forgotten them. Sir George McCrae was arguably Scotland’s most trusted and respected public figure in 1914; sixty years later, no one (save a small band of elderly brothers) even remembered the name.

I guess that anger and pride must be contagious because I took up Sandy Lindsay’s pen and wrote letters to the newly formed Edinburgh District and Lothian Regional Councils proposing the construction of a memorial on the Somme before the last survivor of the battalion died. The response was not encouraging, but it was the start of thirty years of campaigning to set right an old and unjust wrong. Edinburgh, I wrote in one of my letters, should be better than this. Edinburgh, as it turns out, is better than this.

In 1986 Richard Dunning unveiled a magnificent Cross of Sacrifice at Lochnagar, crafted from medieval timber rescued from a deconsecrated church in Durham. By now the annual ceremony of Remembrance at the crater on the morning of 1 July had become the largest event of its kind in the world. In 1989 Richard formed the Friends of Lochnagar, an energetic group of committed helpers, to maintain the site and make it safe for the ever-increasing number of visitors, many of whom were stepping off school coaches directly into the battlefield of 1916. Truly, the men who fought and died there were being appropriately honoured. The Scottish capital, in the meantime, was waiting for its moment!

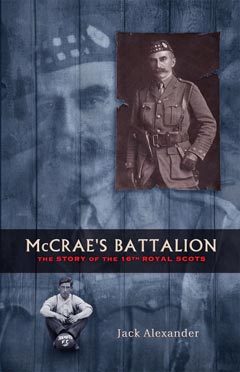

In 1990 I began an ambitious project to tell the true story of the 16th Royal Scots for the first time. A thin version of the tale survived in Edinburgh, but it had retreated into mythology and many of the ‘facts’ were decidedly unreliable – the so-called ‘Hearts Battalion’; no mention of other teams or other sports; no mention of saving the honour of Association Football. And (above all) no mention of the Colonel.

My first tentative efforts at research were thwarted by an almost complete absence of any surviving records. None of the libraries and record offices in Edinburgh had any relevant material. More surprising was a disturbing paucity of Service battalion documents or photographs at the Regimental Headquarters of The Royal Scots. Further afield, the Imperial War Museum, the National Archives and the National Army Museum had little (if anything) to offer. If the story of McCrae’s was going to be rescued from the past, an archive would have to be created from scratch. Over the course of the next twelve years I meticulously reconstructed the battalion’s long-lost nominal roll and set about tracing the families of what turned out to be the majority of original members – including the descendants of the Sir George McCrae himself. The resulting archive is now thought to be the most detailed collection in the world relating to an infantry battalion of the Great War. From that collection I carved a manuscript, entitled McCrae’s Battalion, which Bill Campbell and Peter MacKenzie of Mainstream Books in Edinburgh decided to publish in 2003. The next time that the City of Edinburgh Council was approached with a proposal for a memorial on the Somme, there would be a very different outcome.